Linking farmers into high-end global value chains typically requires product quality upgrading. Quality upgrading, however, can be difficult in agricultural chains in developing countries due to market imperfections along the chain. Upstream, farmers face acute challenges when accessing finance and other inputs and extension services are often lacking. In rural, typically informal, markets, buyers also hold significant market power in terms of setting prices. Lack of meaningful contract enforcement also poses challenges: on the one hand, a buyer might hold-up farmers and renege on promises to pay price premia for quality; on the other hand, farmers might side-sell to other buyers, thus jeopardizing buyers’ ability to recover costs incurred to support farmers in producing higher quality. The same problems – market power and lack of contract enforcement – appear further downstream at the export gate, often compounded by difficulties in finding buyers and by cumbersome bureaucratic requirements.

In a recent working paper, we provide a quantitative evaluation of the Sustainability Quality Program (the Program) in the Colombia Coffee chain. The Program, first launched in 2003, strives to guarantee the quality and sustainability of the coffee sourced by the multinational buyer.[1] The Program is currently implemented in 14 countries worldwide with over a hundred thousand farmers enrolled. The program is a prominent example of a Voluntary Sustainability Standards (VSSs), such as Fairtrade, Rainforest alliance (RA) or 4C. VSSs have become increasingly popular in global agricultural value chains. In recent years, buyer-driven initiatives, like the program studied here, have emerged in response to certain perceived limitations associated with social and environmental labels (see, e.g., DeJanvry et al. (2015)) and as part of a broader trend in which global buyers reorganize supply chains to achieve greater collaboration with a more limited number of suppliers. To the best of our knowledge, the paper provides one of the very first quantitative evaluations of a buyer-driven VSS.

Our analysis reveals that the Program generated substantial gains for eligible farmers and for the Colombian chain as a whole. We ask three questions: (1) what is the impact of the program on eligible farmers? (2) how large are the gains from the Program and how are those shared between farmers and intermediaries? (3) how does the Program work? That is, can its success be replicated elsewhere?

Impact of the Program on eligible farms

In Colombia the Program was implemented across 80,000 eligible farmers and 1000 villages (veredas) over a period of 10 years. We use detailed administrative data to evaluate the impact of the program. Any evaluation requires comparing outcomes for farmers eligible for the program relative to a counterfactual scenario in which the same farmers were not eligible for the program. Since the same farmers cannot be simultaneously observed with and without the Program, the credibility of an evaluation critically hinges on how the counterfactual scenario is constructed. The main difficulty is typically to overcome selection bias concerns: farmers with better outcomes might select into, or have been targeted by, the Program.

The staggered rollout of the Program across villages allows us to implement a “difference-in-difference” (DID) analysis and overcome the challenges. In a DID analysis, changes in farmers’ outcomes before and after their village has become eligible for the program are compared to changes over the same period of time for similar farmers in villages that were not (yet) eligible to receive the Program. The analysis takes into account any underlying fixed difference between farmers that are eligible to be in the Program at a given point in time and those that are not by looking at changes over time. We focus on an “Intention-to-Treat” (ITT) analysis that compares eligible farmers – i.e., those that could have joined the Program irrespective of whether they joined or not – to farmers not yet eligible.[2]

This analysis reveals that approximately half of the eligible farmers joined the program. Eligible farmers upgraded their plantations, expanded land under coffee cultivation, increased quality and received higher farm gate prices. Eligible villages also saw an increase in the number of farmers cultivating coffee – which further suggests that the Program made coffee cultivation more attractive in general.

Quantifying the impact of the Program on the coffee chain

What are the gains of the Program? And how are those gains shared between farmers and intermediaries along the chain? Answering these questions requires understanding how the Program changed both the demand and the supply of quality coffee along the chain.

The program pays a price premium of approximately 10% relative to prevailing farm gate prices. Since the Program support also increased production, the overall profits of farmers that joined the Program increased by 15%. Farmers that did not join the program were not affected by the Program.

The Program exclusively sources high quality, supremo, coffee. At the export gate, the Program pays a 20% (10%) price premium relative to standard coffee (supremo quality). The Program created its own supply, i.e., it did not displace supremo coffee that was previously sold to other buyers. Given the combined effect on aggregate supply of supremo coffee and the price premium, we estimate that the Program increased profits in the Colombia coffee regions in which it was rolled out by about 30%. At least 50% of the additional surplus created by the Program thus accrued to the farmers.[3]

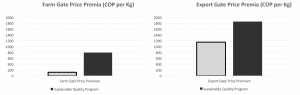

The Figure reports the average price premium (in Colombian Pesos) per kilo of supremo coffee relative to standard coffee at the farm gate and at the export gate. The grey bars depict the price premium in the market. Despite a substantial price premium for supremo coffee at the export gate, farmers are not paid a significantly higher price for the type of beans that end up being exported as supremo. The black bars show the price premium in the Sustainable Quality Program. The Program pays significantly more at the export gate and a very significant share of this additional price premium is paid to farmers. Source: Authors’ calculations form various transactions level data.

How does the Program work?

Finally, we ask how the Program works. This is perhaps the most important, but also subtle, part of the analysis. While the exact impact of similar Programs will inevitably vary across implementers and beneficiaries, understanding the mechanisms behind the program success is key to draw lessons that could be applied elsewhere.

The Program is a bundle of contractual arrangements involving farmers, intermediaries, exporters and the multinational buyer. At the farm gate, the Program provides training, extension services and access to inputs for plot renewal to support quality upgrading. The Program also commits to purchase from Program farmers all the production that satisfies certain quality requirements at a fixed price premium. Program farmers have the option (but not the obligation) to supply the multinational buyer.

A critical feature is that the contract between the multinational buyer and the exporter/program implementer specifies the price premium to be paid to farmers. The Program is thus a form of vertical restraint.[4] Relative to the market and to other non buyer-driven VSSs, the vertical restraint improves the transmission of the quality price premium from the export gate to the farm gate (see Figure 1). In particular, while other non-buyer driven VSSs also require farm gate price premia, the lack of demand commitment from a buyer implies that not all certified production is sold at the certification premium. The buyer “demand commitment” implies that the entire farm gate program premium is paid to farmers.

Discussion, open questions & opportunities

The analysis leaves open a number of important questions which can be answered with further rigorous quantitative analysis. First, can the vertical restraint be successfully imported in other contexts? Although the vertical restraint is perhaps the most critical innovation of the Program, it might be difficult to replicate it. In the vertical restraint, the buyer needs to trust the exporter that farmers are being paid the contracted premium and, conversely, the exporter needs to trust the buyer that the larger export premium will be honoured. Buyers that are either smaller or that can’t pay price premia as large as the Program buyer might struggle to sustain a vertical restraint.

Technology might be coming to help – however. Digital platforms (e.g., those based on a blockchain) might improve transparency and could enable buyers and exporters to directly contract on the price to be paid to farmers even at lower scale than those in the Program – particularly when farmers are directly involved on the digital platform. The digital platform per se won’t help in formally enforcing contracts, but it might create an environment in which reputational forces allows parties to build trust more effectively. To the extent consumers are willing-to-pay for a higher price paid to farmers, digital platforms can also expand the size of the cake and further facilitate the emergence of vertical restraints as the one studied here.

Plenty remains to be learned about which mix of Program features generates the most cost effective impact: is the price premium critical? Are extension services – which might be hard to organize for smaller buyers – critical to the program success? Those are example of smaller, more targeted, questions that RCTs are well-suited to answer in a rigorous way in the particular context in which they are being posed.

More broadly, the evaluation described here was conducted combining administrative datasets collected, as part of its routine operations, by the Federacion Nacional de Cafeteros – the Colombian Coffee board and Program implementing partner. The study provides an example of how existing data can be leveraged to better understand the impact of existing Programs and learn lessons that can be taken to other contexts. Partnerships between industry practitioners – NGOs, companies, governments – and academics can mobilize and analyze existing data to find out what works and gain insights into how to achieve more equitable and sustainable supply chains.

ENDNOTES

[1] The analysis entirely relies on data obtained, as part of a research agreement protected by a confidentiality agreement, from the Federacion Nacional de Cafeteros. None of the data was obtained from the multinational buyer. The study is entirely independent and was funded by research grants raised by the Principal Investigators. Due to the confidentiality agreement the multinational buyer and other certification programs won’t be named in this blog.

[2] The evaluation strategy relies on what the literature on Program Evaluation in economics refers to as a “Natural Experiment” – i.e., a research design that relies on naturally occurring variation to approximate what a “controlled” experiment, i.e., a Randomized Control Trial (RCT) would achieve. In a RCT villages would have been randomly assigned to the program (at least for some period of time). The random assignment would have further attenuated concerns that observed differences in outcomes after the Program could be due to selection. In recent years RCTs have emerged, not without controversy (see, e.g., Deaton and Cartwright (2018)) as the gold standard for Program Evaluation in development. While not based on a RCT our evaluation is at scale (i.e., we evaluate the program in all villages and over a 10 year horizon) and didn’t interfere with operations on the ground. We discuss below promising avenues to use RCTs in the evaluation of similar programs.

[3] A large share of the increases in costs to produce quality coffee is incurred to remunerate additional labor needed to carefully harvest coffee cherries. Our welfare analysis thus likely understate the welfare gains from the Program, since we account as costs what are enhanced labour opportunities for typically disadvantaged harvest workers.

[4] Vertical restraints are common contractual forms in many supply chains in which the contract between a manufacturer and a retailer constrains the price that the retailer can charge to consumer.