Why look at forest-focused supply chain policies?

The expansion of agricultural areas remains the most pressing threat to tropical forests worldwide. As forests are lost and degraded, substantial amounts of carbon are emitted into the atmosphere and critical habitat for biodiversity is lost. Impacts on food and water security to nearby communities can also be severe. Conversely, enhancing tree cover on already cleared farmland contributes to addressing the massive climate challenges we face, potentially creating more habitat for biodiversity or food and income sources for communities.

Since many of the agricultural products grown in recently cleared areas end up in international markets, especially markets that care about deforestation, many major food import companies have made commitments to stop sourcing products associated with deforestation. Others have committed to net-zero deforestation, allowing for some products associated with deforestation to enter their supply chains with a goal to offset impacts by encouraging reforestation in other places. Yet others have committed to encouraging both zero-deforestation and reforestation within sourcing regions. Such “forest-focus supply chain policies” (FSPs) often include social safeguards and livelihood targets, though their primary focus is forest conservation. The focus on conservation over livelihood outcomes can create tensions between the conservation effectiveness of these FSPs and their equity.

Mapping and reviewing the evidence base

Our review examines both the conservation outcomes (deforestation, reforestation, and fire occurrence) and livelihood outcomes (target commodity, farm and household income) of FSPs. FSPs can be implemented through a variety of instruments, such as the use of market exclusion mechanisms (excluding suppliers based on undesirable production practices, e.g., deforestation) and/or codes of conduct and certification requirements (setting criteria that farmers should meet for inclusion and/or preferred market access). Our review focused on implementation mechanisms that pertain to forest-risk food commodities: coffee, cocoa, oil palm, soy, and beef/cattle production.

We searched the peer-reviewed literature from 2000-2020 in Web of Science and Scopus and identified 31 papers, comprising 37 cases, that contain rigorous evidence about the impacts of FSP implementation mechanisms in food supply chains. We treat each case as the result of a specific FSP mechanism for a specific commodity within a given region. So, if a certification like the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) was examined in Malaysia and Indonesia separately, those outcomes would comprise two different cases.

What are the existing outcomes of forest-focused supply chain policies adopted by food companies?

More than half of the cases included in our study found conservation and livelihood benefits resulting from the FSP mechanisms. Positive livelihood outcomes were more common than conservation additionality. In cases that examined livelihoods, 65% found improvements in farm income and 53% found improvements in household income. In cases that examined conservation, 43% found improvements in deforestation or reforestation. However, no studies found a reduction in fire occurrence.

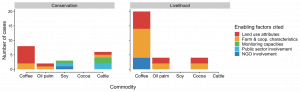

We identified some notable differences across commodities. For coffee and cocoa FSPs, which were implemented through certifications and codes of conduct, improvements in farm income occurred through increases in crop yields on coffee and cocoa farms that have adopted certifications or codes of conduct. However, in some cases adoption of certifications led to a reduction in net household income as farmers increasingly specialized in the certified commodity and spend more on food purchases. In these production systems, existing land use attributes, especially whether or not farms were already adopting agroforestry or monoculture systems, and the characteristics of the producers and cooperatives alongside NGO involvement, especially how well-organized cooperatives and NGOs were in marketing the attributes of certified products or passing along benefits to farmers and communities, all played an important role in influencing the conservation and livelihood gains (Figure 1).

Existing land use practices and farmer attributes were also found to be important for oil palm FSPs, for which the evidence base is focused on RSPO certifications and zero-deforestation behaviors. Studies found that large plantations that have little forest remaining were more likely to adopt RSPO certification, which reduced the avoided deforestation benefits of such schemes and points to how small farmers are often de-facto excluded from certification schemes. Livelihood impacts from RPSO in oil palm farms are highly influenced by the age of trees and, like all crops, the varieties used prior to adoption of the certification. Where yield gaps are high due to older trees and lower yielding varieties, participation in the certification can lead to major improvements in yields and income.

For soy and beef/cattle FSPs, which were implemented through market exclusion mechanisms, public sector involvement in monitoring was thought to have been critical to the success of these mechanisms, whereas limitations in monitoring in relation to the supply chain complexity was thought to be a factor reducing the conservation compliance and additionality associated the beef market exclusion mechanisms.

Figure 1: Enabling factors for additionality cited in sufficiently rigorous cases by commodity and type of outcome. From Garrett et al. 2021.

Most existing studies focus on measuring the additionality of a policy. That is, its impacts beyond business-as-usual land use practices. Yet, there is a need to study compliance and spillovers as well, since these aspects have different implications for understanding the effectiveness of the policy in meeting an individual company’s supply chain goals versus its ability to achieve net increases in tree cover or improve farmers’ financial wellbeing. A supplier can be compliant with the policy, but have zero additionality if his or her practices were compliant with the rule before it became into effect. Compliance might foster additionality (i.e., increased forest conservation in situ), but induce negative spillovers, as non-compliant farmers might be forced to move outside of the jurisdiction. These displacement effects can have important equity implications, as smallholders might have limited resources to comply with the policy. Thus, compliance might be critical to the individual company supply chain effectiveness, but does not ensure broader effectiveness.

Another critical gap in the literature is that conservation and livelihood impacts are rarely studied in tandem. Thus, the on-average positive results here may mask major tradeoffs or conversely, under-represent the potential benefits of FSPs. In the five existing cases that address both types of impacts, there are no clear tradeoffs or synergies that emerged, but rather, most found an improvement in one outcome (conservation or livelihood), and no change in the other.

Overall, existing studies are still clustered in a few geographies and methods for assessing FSP impacts differ widely. These conditions greatly inhibit our ability to generate more general understanding of the conditions under which sustainability standards might success in improving conservation and livelihoods. Going forward, agreement by both researchers and practitioners on best practices for assessing outcomes of FSPs is urgently needed so that attention can be directed to efficiently filling the many knowledge gaps presented in this analysis in ways that are comparable across initiatives and regions. A research focus on FSPs should not come at the expense of additional research on how public governance can be improved to enhance conservation and rural livelihoods. Nevertheless, given the continued popularity of supply chain approaches, especially in the context of increasing policy efforts to halt import-driven deforestation in the global North, make it pressing to understand how such approaches can be improved to ensure they generate benefits to both people and nature.