Trapped in an unsustainable food system

Food is essential for everyone. But our global food system is not sustainable. It is not fit for purpose considering the future generation’s right to feed themselves and threatens to destroy the living conditions in areas where millions of people are living – the delta regions in the world, the forest areas, the regions with already high risks of drought and flooding. I feel trapped in that system. Many options that could mitigate my carbon footprint are out of reach. Off-the grid heating? Recycling of plastics? Reducing my international travel? I can adjust some things in my way of living but not enough to ‘fix the system’.

Similarly, firms, even large ones, are trapped in the food system. Even when they genuinely want to change it for the better, they can’t change the fundamental flaws of the system. Ultimately firms need to be competitive in the market in order to survive. That market system has some positive drivers of change when, for example, consumers of their products can favour or disfavour products based on sustainability attributes. But the market system has many negative drivers for unsustainable, short-term benefits, like the yearly profit that shareholders demand on their investments.

Certification systems, social capital and collective action

Within this complex field of contradicting market drivers, certification has emerged as an institutional arrangement by which firms try to balance positive and negative drivers, and reconcile the good will of the company and the good intentions of consumers with the drive for shareholder profit. Certification provides niche markets where higher consumer prices can cover the increased costs of sustainably sourced products.

Certification systems, like Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance and organic agriculture, can build social capital in the food system – they are the crown jewels that embody collective action, coordination and investment but they are increasingly under threat. It is easier to destroy this social capital than to build it up. For example, negative footage in the press (child labour, low wages, corruption of cooperative leaders) can rapidly destroy its credibility and legitimacy both for consumers and firms.

Impact evaluation for credibility

The reliance of certification systems on credibility and reputation means that firms producing or using certified products in their business pay serious attention to impact evaluation. Certification systems need to prove that the products indeed deliver what they promise, in a way that is robust enough to convince sceptical outsiders. Consumers of certified products expect them to have specific positive social or ecological attributes. And many firms need assurance that by procuring certified products they reduce the risk of reputational damage.

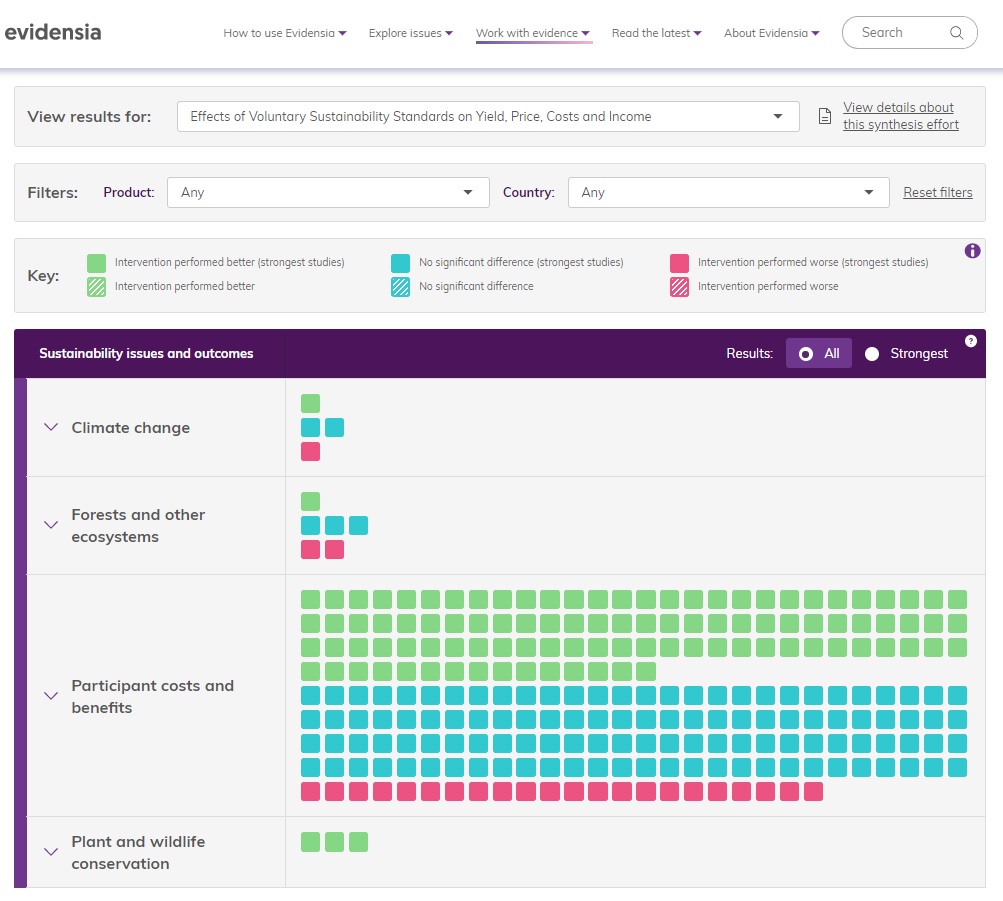

Therefore, a large (perhaps disproportional) part of published research on sustainability in food production concerns the impact of certification. This research is limited to a small range of commodities that represent just a fraction of our food consumption (especially, coffee, cocoa and tea). In June 2019, the ISEAL Alliance launched the Evidensia website which contains nice interactive charts that give an overview of this body of research.

The charts suggest that overall there is a positive effect of certification-related activities in key environmental areas (e.g. plant and wildlife conservation) but also many studies that find no significant effect on farms and farmers being part of a certified or a non-certified supply chain (and for the workers on these farms). Outcomes more directly linked to the specific crop are more prone to show positive effects of certification, while outcomes that are the result of multiple other influencing factors tend to show that there are no meaningful differences between certified and uncertified farms.

Measuring household income effects: Sophisticated but uninformative

In the accompanying publication Effects of Voluntary Sustainability Standards on Yield, Price, Costs and Income in the Agriculture Sector, the Evidensia team concludes that ‘future research efforts [..] should centre on net household income as an important measure of overall economic wellbeing’. This goes against the advice that I and my colleagues, Sietze Vellema and Lan Ge from Wageningen University, gave in an article in the 2014 IDS Bulletin Rethinking Impact Evaluation for Development, titled The Triviality of Measuring Ultimate Outcomes. We argue that this focus on household income might be unwise, not only because the outcomes may prove to be undetectable under real-world measurement constraints (heterogenous package of support activities; high variance due to diversified livelihood activities; low effect size and need for high sample sizes; influence of spill-over effects when comparing between groups, etc.) but also because the learning effect (i.e. How to get better results of certification?) is better served with indicators that are directly related with the activities on-the-ground (farmer training, on-farm prices) and compare different intervention options instead of comparing with an unsupported control group.

In two recent blog posts, Cocoa Life and Ipsos discuss the practical limitations of measuring the effects of sustainability efforts. They present six tips, that reflect the real-world conditions of impact research, one of which resonated directly with the above concern ‘Key indicators are not learning tools: High level indicators of success are great for communicating impact, but less good for understanding how and why an intervention works, or doesn’t work’. Five years after our Triviality paper, I feel even more strongly that it is unwise and a waste of resources to make household income effects the prime indicator of interest of impact studies. I think that impact research might need to shift its focus to explore new policy options within the certification process, looking at crucial elements of the certification process that need to be improved to remain relevant and credible. At least two areas present opportunities to compare and improve.

Premiums and wages: Improve or perish

While measuring incomes may be trivial, improving incomes of the cocoa and coffee producers is definitely needed. In contrast to Fairtrade, certification systems like Rainforest Alliance do not want to interfere directly in the price negotiations between the buyer to the farmer. Paying a cash premium is demanded by the Rainforest Standard, but without specifying how much it needs to be. But in the cocoa sector, with a world price of around GBP 2,000/ton and first-line buyers in control of distribution, most farmers barely notice the price premium (estimated in around 3.5%). Even when this farmer-level premium would triple, the final consumer prices for chocolate would barely be affected. Why not make the level of premium and wages transparent (implicitly naming and shaming the lagging ones)? Why not exploit and experiment with differences between buyers/traders, and compare sites were the premium is paid in different ways? For example, the premium could be made explicit as a cash voucher instead of being implicit in the buyer’s price, or the premium could be as cash to complement farmer income or earmarked as funds for collective action. The reality of overlapping certifications (farmers certified both by Fairtrade and Rainforest Alliance) creates a good starting point for this type of impact research.

Similarly, improving wages is key. Certified producers need to move beyond the obligation to pay their workers the legal minimum wage. The minimum wage is in most countries insufficient to raise and feed a household. Country and sector specific living wage benchmarks exist that set the bar. How can certification systems create the incentives and momentum for wage levels to improve? Certification systems could require producers to measure and report the gap between wages paid and the living wage, setting targets to make progress visible.

The problem both for the absence of a significant price premium and the low wages paid to workers is the lack of effective coordination and transparency in the value chain. A problem of collective action. Certification systems provide the social capital to change this but need to find more effective mechanisms to transfer the willingness of end-consumers to pay into real change into better outcomes for farmers and workers. Without these field-level effects, certification risks becoming a sophisticated way of working without real relevance in the global food system.